The Dutch and the Atlantic Slave Trade

The Atlantic Slave Trade was the largest forced migration in world history. The trade began soon after Europeans landed in the Americas in 1492 and continued for centuries. Forty thousand ships brought enslaved Africans across the ocean during that time. Twelve million Africans were captured, shipped across the Atlantic in cramped, filthy, and often deadly conditions, and then enslaved in the Americas. That comes to 80 Africans enslaved per day, every day, for 400 years.

See this page for an interactive timeline of the Atlantic slave trade.

Like other European nations, the Dutch were heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade. Dutch ships carried around 500,000 enslaved African people to the Americas between 1596 and 1829. Some landed on the Caribbean islands of Curaçao and St. Eustatius to be shipped to Spanish colonies. Others went to Suriname on the northern coast of South America, where they labored on sugar plantations. When the Dutch came to New York, they brought the slave trade with them.

Europeans Come to New York

In 1609, English explorer Henry Hudson led a Dutch expedition to try to find a route to East Asia through the Arctic Ocean. The mission was a failure. But it made Europeans aware of the existence of the waterway that became known as the Hudson River.

Some 12 years later, in 1621, the Dutch West India Company established a settlement along the Hudson River known as New Netherland to trade in beaver furs and other items. The colony eventually stretched from southern Massachusetts to Delaware. The company was supposed to monopolize trade in order to boost the economic power of the Netherlands against the English and Spanish colonies.

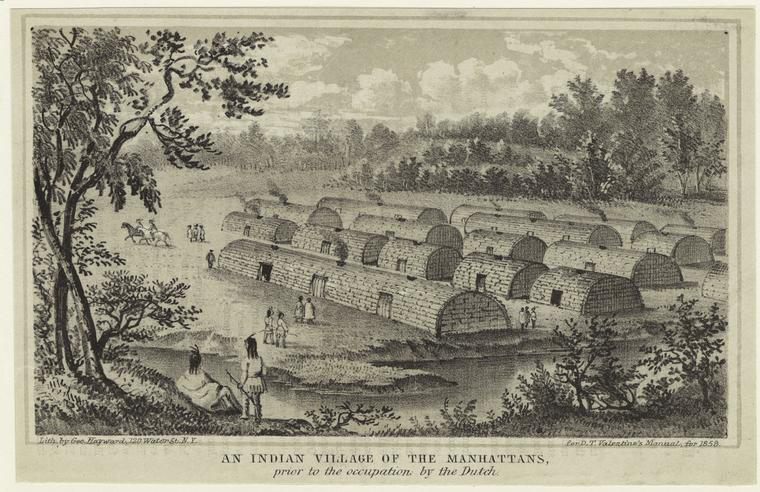

The Dutch conducted a brisk trade with the Algonquin/Lenape people, who were eager to acquire metal European tools. In 1626, the Dutch used these trading relationships to acquire ownership of the island of Manahatta, though how they did so is still disputed. Peter Miniut, the leader of the Dutch West India Company, claimed to have paid the native people $24, or about $500, for the island. It is likely, though this trade never happened, or that Miniut misrepresented it in his records. Practically the Dutch had the power to take the island, and they did so.

The Dutch controlled New Amsterdam until 1664, when the English seized the city and renamed it New York. They ruled the colony until the American Revolution in 1775.

The First Black Resident of New York

Black history in the place that became New York City starts with Jan Rodrigues or Juan Rodrigues. Born of an African mother and a Portuguese father, Rodrigues was a free sailor from Hispaniola in what is today the Dominican Republic. He was known for his facility with languages and was hired in 1613 as a translator by a Dutch trading expedition to Manahatta Island led by Captain Thijs Volckenz Mossel.

Rodrigues quickly learned the Algonquin language of the Lenape people. He became an interpreter and helped establish trade agreements. When the Dutch vessel left, Rodrigues stayed, and married a Lenape woman. That made him the first nonindigenous permanent resident of Manahatta. He remained the only one until 1621, when the Dutch West India Company built its settlement on the Hudson River. Soon thereafter, the Dutch brought African laborers to the colony.

Enslaved African People in New Amsterdam

Some researchers think that the first group of eleven enslaved Africans were brought to New Amsterdam, the capital of New Netherland, in 1626. Others suggest the Africans may have been part of the crew of a pirated Portuguese ship brought to New Amsterdam in 1627.

In any case, historians agree that the men hailed originally from Congo, Angola, and the island of São Tomé. Their names were Paulo d’Angola, Simon Congo, Anthony Portuguese, Jan Francisco, Little [Kleyne] Manuel, Big [Groot] Manuel, Manuel de Gerrit de Reus, Garcia d’Angola, Peter Santomee, Little Anthony, and Jan de Fort Orange. Three African women were brought to New Amsterdam two or three years later. More quickly followed.

This first group of Africans were forced to work for the Dutch West India Company and were housed at the Saw Mill in a camp referred to as Quartier van de Swarten (Quarters of the Blacks). It was located along the East River in the vicinity of 75th Street.

On February 25, 1644, eighteen years after their arrival, the eleven enslaved workers petitioned the local Dutch authorities for their freedom. They argued that they had worked long enough and could hardly support their families.

The Africans’ request was granted, with conditions. Each one received land in return for delivering one “fat hog” and twenty-two and a half bushels of corn, wheat, peas, or beans to the Dutch West India Company every year. The Africans also had to serve the Company on request, though they were to be paid for their labor. Failure to comply with these requirements meant re-enslavement.

The newly freed men’s wives were also emancipated. However, their children were still considered property of the West India company. The manumission document stated that “their children at present born or yet to be born, shall be bound and obligated to serve the Honorable West India Company as Slaves.”

Free and Not Free

The legal status of Africans was not uniform during this early period. Some were free, others were half-free, and still others were enslaved. Even enslaved Africans in New Amsterdam in the early 1600s often enjoyed some of the same rights as white residents. Africans could own property and bear arms. They could engage in the same commerce, both legal and extralegal, as whites.

Beginning in 1655, however, colonial authorities transformed New Amsterdam into a slave trading port and increased restrictions on the African residents. The English restricted the rights of enslaved people further when they seized the colony in 1664.

From 1643 to 1716, approximately thirty land grants were owned by free Black men and women. Authorities hoped that these properties, located in the unsettled area north of New Amsterdam, would serve as a buffer zone between the village and Native American settlements.

The Africans’ plots ranged from one to twenty acres. They were located a mile from New Amsterdam, beyond the palisades that surrounded the town. Their collective 300 acres stretched from Fifth Avenue and 34th Street to the Bowery Road near the Collect Pond, also called Fresh Water Pond—the town’s main source of drinking water, in the vicinity of today’s Canal Street.(See the discussion of Five Points in tour.)

One Black man, Manuel de Gerrit, owned much of today’s Washington Square Park. Paulo d’Angola’s land stretched from Minetta Lane to Thompson Street. By the 1640s what was known as “the land of the Blacks”—a kind of Black frontier—partially covered what today are Chinatown, Little Italy, SoHo, NoHo, Greenwich Village, and Union Square, north to 34th Street.

The last grant was owned by Francisco Bastien, whose family sold the property at 34th Street following a 1712 law that prohibited blacks from leaving real estate to their descendants.

"the Land of the Blacks"

The larger area represents the entire area owned by free Black people, and the darker red section in the middle represents the area that was known as "Little Africa" for its high concentration of people of African descent.

By 1660 about 250 Africans and their descendants, most of them enslaved, lived in New Amsterdam.

Slavery in New York is Abolished

New York State passed an act to gradually abolish slavery in 1799. It manumitted, or freed, the last enslaved people in 1827.

But slavery remained an intrinsic part of economic life in the state through the end of the Civil War in 1865. New York businesspeople continued to profit from the products of the slave trade like sugar and molasses imported from the Caribbean, and from cotton imported form the US South. Some researchers believe that 40% of profits from American cotton came to New York via shipping businesses, financial firms, and insurance companies. Cotton was mostly raised by enslaved people until the end of the Civil War in 1865.

1834 Riots Targeting Black New Yorkers & Abolitionists

In 1834, white mobs carried out violent attacks targetting black New Yorkers and abolitionists. Click on the red dots on the map below to learn more about the targets of these racist attacks.